2015 Most Endangered

|

Firmin Desloge Hospital and Desloge Chapel

Completed between 1931 and 1933, the Firmin Desloge Hospital Tower and Desloge Chapel (“Christ the Crucified King Chapel”) are among St. Louis’ most recognizable buildings. Designed by Study & Farrar with Arthur Widmer, and Ralph Adams Cram, the buildings are fabulous examples of two twentieth century approaches to the interpretation of Gothic Revival style. They are also beautiful, sound, enviably located, loved by the community, and ripe for redevelopment. Their new owner, SSM Health Care, may be planning to tear them down when a new hospital is developed on adjacent land. Landmarks Association has authored two statements regarding the importance of the buildings and provided them to SSM leadership. The second letter outlined the fantastic opportunity that the buildings presented for adaptive reuse and was signed by a very wide range of prominent individuals, organizations and area stakeholders.

|

St. Bridget of Erin

The cornerstone for St.Bridget of Erin was laid in 1859 and the church was regarded as the mother church of Irish Catholics in St. Louis. Located in the 5th Ward, which is not subject to preservation review, St. Louis preservation ordinance was powerless to prevent the demolition of the building. Despite scrambling effort by Landmarks' staff, Board and concerned citizens to find some way to prevent the demolition, the buiding's owner De La Salle Middle School moved forward very rapidly with their destructice plans. In the end, Landmarks was even denied the opportunity to complete a formal documentation of the building before the wreckers showed up. When we started working on the Endangered List, St. Bridget's was intact. It is now just a memory.

|

MO Belting Company (left) and Pevely Dairy Office (Right)

|

No strangers to the Most Endangered List, the Missouri Belting Company and Pevely Dairy have been targets for demolition since St. Louis University originally proposed a plan for a new medical facility in 2012. That plan did not prove to be viable, and the site was never fully consolidated. Now, following the sale of the SLU Hospital to SSNM Healthcare, a plan is emerging for a major new hospital which once again will presumably call for the removal of the Pevely and MO Belting buildings. Hopefully the new buildings will justify the sacrifice with an attractive contemporary design that restores some density to this otherwise windswept intersection. In a city that has a nasty tendency to replace historic buildings with parking lots, the new hospital represents an exciting opportunity to demonstrate that in some cases, "out with the old and in with the new" doesn't have to be a step in the wrong direction.

|

St. Augustine Roman Catholic Church

According to the National Register nomination for St. Augustine's, when its cornerstone was laid in 1896, 10,000 people gathered to watch. Built to serve a booming German Catholic population in the St. Louis Place neighborhood, the church remained part of the St. Louis Archdiocese until closure in 1982. Designed by German born architect Louis Wessbecher (who also designed St. Stanislaus and Bethlehem Lutheran [demolished 2014]), the building has a distinctive German Gothic character and still contains stunning stained glass windows by Emil Frei. Historian Mi Mi Stiritz successfully nominated the building to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986, and it is also recognized as a City Landmark. Unfortunately, neither of these designations has the ability to protect the building from the creeping decay of deferred maintenance and the swarm of vandals and scavengers that have descended since the current owner, Last Awakening Christian Outreach, stopped using the building. A recent inspection by a concerned activist elicited the following description: "open windows, rotting roof, missing guttersm melting floor; the rectory, which had been in good shape, has been pillaged of its windows." St. Augustine's is yet another catastrophic example of the plight of St. Louis' ecclesiastical architecture, particularly in struggling areas of the city's north side.

|

4225 Duncan, Remains of the Mutual Brewing Company

In 201, CORTEX tore down the 1919 Case Threshing (Brauer Supply) building at Forest Park and Boyle. A few months later, they tore down the attractive office of the former Empire Brewery at 311 S. Sarah. The next buildings to be destroyed are the remains of the Mutual Brewing Company at 4229 -35 Duncan. According to "St. Louis Brews, 200 Years of Brewing in St. Louis," construction of Mutual began in 1912. Historic images demonstrate that the brewery complex was a very substantial operation, but within a year of completion, angry creditors initiated bankruptcy proceedings and by 1917 the company's assets were auctioned. The following year, Prohibition began and beer was never again brewed at the site. While CORTEX likes to use words like "sustainable" and "innovative" to describe itself, it seems ironic that so many of the interesting and unique buildings that already exist in its redevelopment zone are regarded as impediments rather than assets.

|

Central High School (Originally Yeatman), 3616 Garrison Avenue

Designed by William Ittner in 1902, Yeatman was the match for McKinley, which was constructed simultaneously on the south side. Ittner’s first high schools, these facilities were constructed to alleviate crowding at the original Central High School , which by 1900 was overwhelmed. Central is an illustration of Ittner’s preference for “Jacobethan” design with five story stair towers flanking a monumental entry, limestone friezes, quoins, belt courses, mullions and window surrounds. The building was closed in 2004 and sat empty though largely intact for eight years before a developer hired Landmarks Association to nominate the building to the National Register of Historic Places in advance of rehabilitation. While the listing was successful, the rehabilitation never took place and the building was subsequently overrun by thieves and vandals. In 2015 the SLPS approved an application to demolish the building for brick salvage. That plan also fell through. Now the building stands open to the elements with all the copper roofing, flashing, gutters and even some stone window surrounds stolen.

|

Hempstead School

A carryover from last year, Hempstead School continues to languish and deteriorate. In May of 2014, a fire swept through the upper floors of the building in the Hamilton Heights neighborhood of north St. Louis. Vacant since 2003, the Ittner-designed school was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2007, the year it turned 100 years old. Despite efforts by SLPS Real Estate Director Walker Gaffney and Landmarks Association to find a new owner for the building (structurally sound, but severely damaged by the fire) so far nobody has stepped forward with a viable plan for reuse. While Mr. Gaffney’s proactive approach toward marketing vacant schools (illustrated by the public tours and the solicitation of input that took place over the course of last summer) is generating positive outcomes for a number of important buildings, Hempstead’s condition and location pose significant impediments to redevelopment.

|

Buildings in the Footprint of the Proposed Relocation site for the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency

|

While the retention of 3,100 NGA jobs in the city is a necessity, the relocation of the facility to north St. Louis will certainly have a negative impact on some historic architecture, residents, businesses and institutions in its path. While many residents have accepted buyout offers, others have resisted relocation and the threat of eminent domain. In at least one case, the city has agreed to physically move a house to satisfy a resident. While expensive, such a practice could be seen as an equitable solution for people who want to remain in their homes. As Paul Hohmann of the Vanishing StL Blog points out, if done strategically such a practice could actually strengthen surrounding blocks by filling in vacant lots.

The largest historic building that is threatened is the former Buster Brown factory at 1526 N. Jefferson. This building was listed in the National Register by Landmarks’ Association in 2004, the building was built for the LaPrelle-Williams Shoe Company and acquired by Brpwn in 1904. Today the building is in good shape and is occupied by a company that sells countertops and cabinets. This and other buildings on the fringes of the project area could be spared by some flexibility in the site plan. Again as Paul Hohmann points out, the NGA’s own specifications require a minimum footprint of just 50 acres, not the 99 that comprise the current proposal. Of course, given this consideration perhaps it is legitimate to ask how many buildings could have been saved and residents left in place by using the adjacent 33 acre Pruitt-Igoe site (already vacant and owned by the city) to make up the lion’s share of the needed land?

|

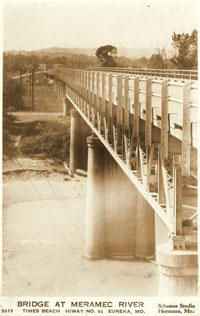

Meramec River Route 66 Bridge

Located in Missouri's Route 66 Park (St. Louis County), the bridge was constructed in 1931-32 to serve the needs of America’s new federal highway. Established in 1926, U.S. (Route) 66 is an international attraction that draws thousands of tourists each year. This is good news for Missouri and a solid economic reason to embrace surviving historic resources that tell the story of this iconic highway. The Meramec River Bridge is a unique three-span, rigid-connected Warren deck truss. With such a bridge, the trusses are below the deck; If you flipped it upside down, it would look more like the Chain of Rocks Bridge in St. Louis, which carries Route 66 across the Mississippi River. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places as an engineering achievement and for its association with transportation history, the bridge is the only Warren truss span that serves Route 66 in Missouri. Missouri State Parks has agreed to take over ownership of the bridge and preserve it as a component of the surrounding Route 66 State Park if an endowment of $650,000 can be raised by the end of 2016. Currently many entities including the Route 66 Association of Missouri, Great Rivers Greenway, Trailnet, Landmarks Association of St. Louis, St. Louis County Parks & Recreation, the Missouri Open Space Council and Missouri Alliance for Historic Preservation are working to raise the needed funds. If you would like to make a donation to the effort visit www.gofundme.com and search for “Route 66 Bridge.” If the money can’t be raised, the bridge will be demolished in 2017.

|

Henry L. Wolfner Memorial Library for the Blind, 3842-44 Olive Street

A carryover from last year’s list, The National Register listed Wolfner Library Complex consists of two buildings constructed in 1898 and 1904 by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge and Mauran, Russell & Garden respectively. Originally built as the Lindell Exchange for the Bell Telephone Company, the buildings were repurposed in 1938 and put into service as the first "stand alone" library for blind in the United States. By 1940 only the Library of Congress exceeded Wolfner in its collections and circulation of Braille and "talking" books. The facility closed at this location in 1971 and merged with the Missouri State Library in Jefferson City in 1985. Located on a block of Olive adjacent to Grand Center and St. Louis University, decades of demolition have rendered the area desolate and the library virtually devoid of context. Currently neglected and condemned, the Wolfner Library, once a symbol of St. Louis' progressive nature, appears to be on the verge of disappearing.

|

James Clemens Jr. House, 1849 Cass Avenue.

This formerly grand mansion designed by Patrick Walsh for James Clemens Jr. in 1858 bears little resemblance to the home where a ceremonial signing of two aldermanic bills in support of developer Paul McKee's North Side Regeneration plan took place in 2009. Every year there is less and less to save of the Clemen's Mansion and its associated chapel. Open to vandals and the elements for years, the buildings offer a sad commentary on how even high profile and highly significant buildings are allowed to fade into oblivion in a city that lacks the will and authority (or at least selectively wields them) to hold derelict absentee property owners like O’Fallon MO based Northside Regeneration accountable for the condition of their buildings.