The Glories of Germanhood: A History of the Turnverein in St. Louis. Chapter One

Over the next several weeks, Landmarks Association will be posting chapters of an essay on the history of the turnverein movement in St. Louis, Missouri. The detailed history of the movement was researched and placed into a final report over the course of nearly a year by our former intern, Andrew Wanko. After cutting his teeth writing hundreds of building descriptions for district nominations, Andrew was ready for a new project. Our office asked if he would like to research the various turnvereins in St. Louis. Andrew enthusiastically replied "Yes" and then asked, "What's a turverein?" He quickly learned every detail of the movement and during our spring lecture series Andrew's talk was by far our most popular. We hope you enjoy this fascinating cultural history of our city over the next few weeks!

Chapter One: The German Beginnings

1. The Creation of a Unified Movement

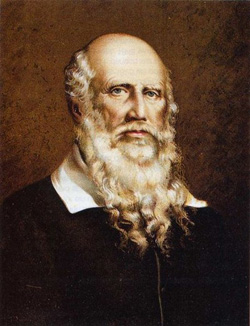

The Turnvater: Friedrich Ludwig Jahn

|

| Friedrich Ludwig Jahn |

Friedrich Ludwig Jahn was present at the first rumblings of what would soon become an ideological earthquake sweeping the German Confederation, an association of thirty-nine independently governed German-speaking states. Jahn was born in the largest Germanic state of Prussia in 1778, which became one of many satellites to Napoleon Bonaparte's vast French Empire. As Jahn aged, he saw this occupation of the German Confederation by Napoleon as humiliation to his race. Existing as a pawn of foreign power was an intolerable frustration to an outspokenly nationalistic and progressive man like Jahn. In 1809 Jahn moved to Berlin to become a gymnastics teacher, and he conceived that regular physical exercise could be the catalyst of revival for his countrymen's moral spirit and physical ability. Excellence of mind and body intertwined could become a cultural identity that no one could remove or corrupt.

On Berlin's Hasenheide athletic grounds in 1811, the first open-air gymnasium dedicated to physical and mental rigor through exercise was opened by Jahn and named Turnplatz. The training emphasized gymnastic exercises, but Jahn also endowed it with the social and patriotic duties of maintaining German culture and protecting the German language from foreign influence. Young members were taught to view themselves as heroes of a new movement with unwavering German ideals and the possibility to emancipate the fatherland.

The Spirit Systematized

|

| Jahn Memorial in Forest Park |

Jahn had the audacity, ruggedness, and experience to back up these bold principles. In 1813 Jahn took an active role in the founding of the Lutzow Free Corps, commanding a volunteer force of Prussians into battle against Napoleon's advancing army. After returning to Berlin, he was promoted to state teacher of gymnastics in 1816. In that same year, Jahn systematized and published his beliefs on physical exercise in a work named Die Deutsche Turnkunst, "The German Art of Gymnastics." If a Berlin schoolboy studying this work in 1820 was transported to the gymnastic events of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, he would recognize many concepts almost unchanged. Among endless other contributions to sport, Jahn has been credited with inventing early models of the balance beam, horizontal bars, parallel bars, and vaulting horse.The spirit of physical rigor spread quickly through the German mindset. Gymnastic halls were an effective medium for organizing a strong resistance to French domination, and after Napoleon fell, resistance to the conservative aristocratic families who ran the thirty-nine Germanic states. The gymnastic halls were given the name turnverein, roughly "gymnastic society," and they quickly multiplied outward from Berlin.

A public memorial to Friedrich Jahn can be seen right here in St. Louis. In Forest Park, directly north of the St. Louis Zoo and at the east edge of Art Hill is Post-Dispatch Lake. Near a north and south running path at its western edge is a particularly large bust of Jahn atop a curving monument. It was erected in his memory in 1913 by The St. Louis Chapter of the Nord Amerikanischer Turnerbund (more about them later) on the site of the German Pavilion of the 1904 World's Fair. The monument was created by Robert Cauer of Krueznach, Germany for $14,000, and then shipped to St. Louis.

2. Retaining Principles in a New World

The 1848 Upraising of the German Confederation

In 1848, riots exploded across Europe, including the thirty-nine independent states that made up the German Confederation. The rioters unbendingly demanded a Pan-German national state with liberal economic policies, freedom from censorship, and radical modifications to the working class' rights. The loosely coordinated rebellions showcased mass demonstrations led by well-educated students and intellectuals - exactly the type of men found socializing in Friedrich Jahn's turnvereins.

While vastly popular amongst all the repressed classes, in-fighting between the numerous smaller revolutionary factions proved to be the flaw that the ruling aristocrats were able to exploit. Many rulers of the Germanic states seized the opportunity to strike back efficiently and quickly squelched the flame of revolution. A harsh persecution of any liberal policies began, and turnvereins were quickly set upon as liberal breeding grounds.

The Turnverein's Cross-Atlantic Voyage

|

| Cheering Revolutionaries in Berlin. 1848. |

The appearance of the first turnverein in the United States slightly predates the European events of 1848, but those revolutionaries were the true creators of American turnverein culture. Turnverein introduction across the Atlantic is most widely attributed to a man named Charles Follen, a German political refugee who taught at Harvard University and instituted the first American gymnasium in 1825. It was not his ambition, however, to establish political and cultural centers like those found in Germany, but rather simply to provide a gymnasium for exercise (he resigned being its superintendent only two years later). The vast majority of the American turnverein movement's roots truly sprouted in the most unstable soil of the 1848 European revolts.

Many of the immense number of German political refugees seeking asylum from the harsh persecution of offended German aristocrats fled to the United States. More than one million German immigrants came to America during the 1850s to start life anew. They brought with them their sturdy German ideologies and their love of the shared physical culture turnvereins offered. Societies began immediately appearing across the United States in every major city. Turnvereins first appeared in Cincinnati and New York (1848), then in Philadelphia and Baltimore (1849), and then in an 1850 explosion in which over a dozen were formed. By 1853 there were seventy, and at the close of the decade 157 existed.

Only two years after these German liberals had fought to change the fate of their own lands, they reestablished their culture in a new land on a collective scale with the founding of the Nord Amerikanischer Turnerbund (referred to from here as the "Turnerbund" for ease of reading) in Philadelphia, in 1850. The official language of the organization was German, and all journals, newspapers, and statements were published in it. The Turnerbund cemented the presence of German turnvereins in America and helped societies to band together and flourish. The regular stream of German immigrants escaping persecution provided the Turnerbund with a consistent flow of new members. Many, but not all, turnvereins across the United States joined, and in 1867 the Turnerbund had 148 member societies totaling 10,200 members. By 1894, that number had more than doubled to 314 member societies spread out over thirty-four states.

An 1898 survey of all member turnvereins reveal some impressive facts about membership of the North American Turnerbund

36,651 adult males, 3,760 adult females and over 27,600 scholars (children under 18)

165 professional instructors (65 of whom taught in public and private schools as well)

66,792 volumes total among all society libraries

915 organized youth clubs (debate, art, philosophy, etc.)

78 halls with special funds set aside for medical care and burying cost of deceased members.