The Century Building Demolition: Landmarks Versus the National Trust for Historic Preservation

With some misgivings, Landmarks Board of Directors authorized Executive Director Carolyn Hewes Toft to appear on a panel discussion entitled "Preservation-Based Development: When is Demolition Justified?" at the 2005 National Trust conference in Portland, Oregon. The final description of the session offered the following enticement:Explore the issues in preservation-based development when major rehabilitation of key historic buildings may require demolition of other significant historic buildings. In most cases, preservationists are united in advocating the re-use of historic buildings as a cost-effective revitalization strategy to meet contemporary needs such as housing, offices, and theaters. As revitalization becomes more prevalent in urban cores, how do preservationists deal with proposals to demolish particular historic buildings to gain the rehabilitation of other historic buildings, particularly where there are divergent views about the need for demolition "trade-offs"? Recent controversies in St. Louis, Chicago, and Los Angeles will be discussed.

Held on Friday, September 30 and moved to the ballroom of the Governor Hotel in order to accommodate a large crowd, the session was introduced by Jonathan Kemper, Chairman of the National Trust Board of Trustees who had requested that this topic be covered at the conference. Many people attended the session in order to hear the St. Louis segment, especially after the contentious subject was mentioned from the floor at the plenary gathering of several thousand. The exchange between Carolyn Toft and Richard Moe, President of the Trust, opened with Toft's remarks (see below) outlining Landmarks' long history with the Old Post Office, its environs and our profound disappointment with actions taken by the National Trust that led to the demolition of the Century Building.Next, Richard Moe, who appeared somewhat flustered but not contrite, responded with many of the same arguments and/or rationalizations he expressed in the Post-Dispatch "Commentary" on July 14, 2004. Since then, however, we have been told that the Trust has tightened review of any investment project proposed for its new Market Tax Credits and has also formalized new requirements for review of all Programmatic Agreements signed by the Trust. Somehow, that just doesn't seem to be enough-an opinion shared by many at the conference.

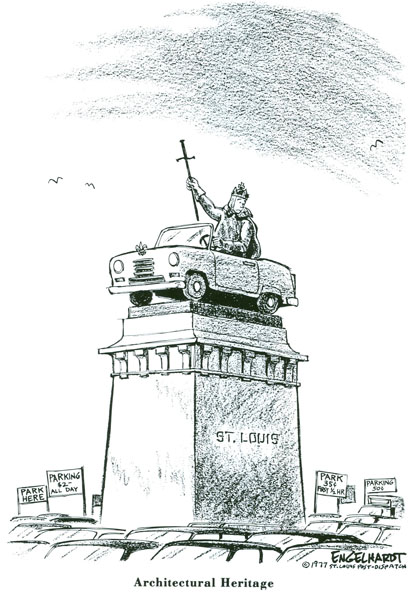

Copyright 1977 Engelhardt in the St. Louis Post Dispatch/reprinted with permission |

Carolyn Toft's Remarks at the Conference

Until the recent demolition of the Century Building, the National Trust and Landmarks Association had a shared history of advocacy. It started, ironically, with efforts in the 1960s to save Alfred B. Mullet's Old Post Office in downtown St. Louis. A decade later, former Trust President Bob Garvey attended a lunch presented by Landmarks where Senator Tom Eagleton announced winners of the national architectural competition. Thanks to the Public Buildings Cooperative Use Act of 1976, the GSA-owned bulwark would become a lively mixed-use project. In fact, Landmarks' Old Post Office Committee received the Crowninshield Award. [This is the highest award given by the National Trust.] But the much-heralded public/private partnership was flawed. The development/marketing team could not agree among its members; competing projects moved forward with more vigor, more direction. Delays pushed the Post Office's formal reopening into late 1982.

Over the years casual conversations with regional Trust staff touched on the failure of the $16 million adaptive reuse of 1982 to bring sustained life to the Old Post Office. We also commiserated about GSA refusal to explore the building's obvious potential as a pivotal light rail station. No concerns, however, were ever expressed about this National Historic Landmark's condition or its detrimental effect on the historic context. Surrounded on three sides by late 19th and early 20th century buildings, the moated and somewhat formidable Post Office sat aloof in a virtually intact, but undervalued, urban space of singular local significance.

After a brilliant spurt in the mid-1980s, preservation-based development in St. Louis had stalled. That all changed with Missouri's historic rehab tax credit legislation-initiated by Landmarks Association and enacted in 1997. Older buildings suddenly became assets, including the nearly vacant Old Post Office and its immediate neighborhood. "Post Office Square" became a major focus of a downtown-planning epic that got underway in late 1997. Landmarks was part of a multi-disciplinary team hired to evaluate streetscapes, building conditions, historic resources, open space and parking needs. The subsequent document officially adopted by the City Plan Commission in 2001 reflected group consensus: no parking would be allowed facing the Old Post Office.

We were therefore stunned when a city-endorsed redevelopment scheme combining yet another adaptive reuse of the Old Post Office with demolition of the adjacent Century Building for a parking garage was presented later in 2001 as a fait accompli, non-negotiable package. No request for proposals had been issued. No counter proposals would be tolerated.

For a short time the Trust's regional office in Chicago shared our concerns. Then, a major staff change was followed by a sudden, incomprehensible decision to support the proposal. In response, we sent an outraged communication in January 2002 to the new Midwest Director: "For the National Trust to capitulate to the expediency of the moment and endorse the [demolition] plan without reservations simply makes no sense. This decision is heavy handed and gratuitous; it negates a generation of working together, mutual support and respect...."

|  |

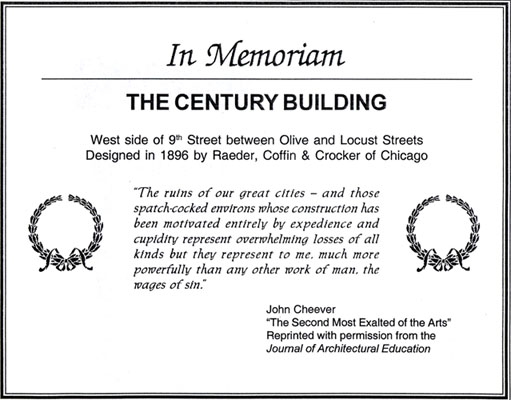

The Trust-supported plan is an urban design and transportation-planning disaster. Architecturally, the Century Building built in 1896 responded elegantly to the Old Post Office with a formal but complex organization. Its Neo-Classical front elevation filled an entire block facing the National Historic Landmark. Existing parking garages located within two to three blocks of the site stand partially empty; a vacant lot with a similar footprint to the Century Building lies directly north of the Post Office; the project is just steps away from a light rail station. Furthermore, the National Park Service's tax credit section had given preliminary approval to a counter proposal that would have reused the entire Century block for a mixed-use project accommodating at least 500 interior parking spaces. St. Louis already had more downtown parking per capita than any other city in the country. The parking-needs issue is bogus.

So is sustainable economic development. Officials waxed eloquently about the first two tenants committed for the Post Office: the Missouri Court of Appeals and Webster University. Although each brings a use highly compatible with the restraints inherent in adapting the National Historic Landmark, it is helpful from an economic development perspective to note that both are already located downtown in historic buildings. Neither contemplates any meaningful expansion of existing services in the near future. More recently, the public library agreed to open a satellite branch at the post office; the main Cass Gilbert-designed building is just four blocks away. Relocation of the small St. Louis Business Journal staff to the post office involves a journey of only two blocks.

Our profound disappointment with the Trust's decision to back the scheme publicly was soon compounded by the announcement that the Trust would in fact become a financial partner by directing New Market Tax Credits to the deal. In response, we visited the Trust office in Washington D.C. We sent certified letters with supporting videos documenting the extensive renovation already underway in the district to all Trustees. Indeed, Landmarks exhausted every possible private approach before taking our disagreement public with an online petition in June of 2004.

More than 3,500 preservationists, architects, planners and concerned citizens from around the country signed the petition. Many volunteered searing comments about the Trust's inexplicable role. "This project violates everything the National Trust is supposed to stand for," said Michael Tomlan, Director of Cornell University's Historic Preservation Planning Program, "They have gone terribly wrong." Martha Frish, former senior real estate and financial associate for the Trust office in Chicago, remarked: "The Old Post Office is important, but so is its context. The justifications by the developer and its public partners [for razing the Century Building] were insufficient three years ago, and they remain inadequate."

In response to a favorable story about the petition, the Trust sent a rebuttal to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Defiantly subtitled "The Facts are Clear: To Save the Old Post Office, the Century Building Must Go," the essay ran on July 14, 2004. Its opening volley presumed the Post Office needed to be "saved." We beg to differ. That battle had been fought and won in the 1960s. Next, the Trust clarified why preservationists must accept the "regrettable but necessary" trade-off: the Old Post Office is a National Historic Landmark while the Century Building was merely listed on the National Register as locally significant. Correct. Also listed as locally significant are the rest of the historic buildings surrounding the Post Office along with dozens of National Register districts throughout the city. The National Register abandoned the isolated icon approach to preservation over thirty years ago. Indeed, so did the National Trust.

Continued support of the outmoded real estate scheme was in direct opposition to everything the Trust professed to believe about preservation in context. It also flew in the face of market realities. By July of 2004 virtually every other building surrounding the Post Office had been or was being renovated--all financed without the Century garage or any activity at the post office. Indeed, to the innocent passerby, the granite fortress could appear fully occupied. Meanwhile, to no avail, a second reputable developer of historic properties cautiously approached the Mayor with a mixed-use proposal for the entire Century block. A team that presented a similar unwanted alternative in 2002 had been harshly rebuffed to the point of intimidation by the city and by the politically connected development team that became the Trust's partner. That political clout extended to the State of Missouri and on to Washington D.C. where past and current members of Missouri's Congressional delegation were enlisted to advance the proposal.

The Trust often reminds its members and the media that the State Office of Historic Preservation and The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation also supported the project. But the Trust is not a regulatory agency; it is supposed to be an advocate. Citing regulatory agencies which might have performed better, but succumbed to political pressure, is a feeble rationale. So are evasive statements from the Trust insisting that their funds will go only toward work on the Post Office itself. All documents view the project as a single undertaking. National Trust subsidy to the project totaling almost $7.5 million in New Market Tax Credits allowed demolition of the Century Building to proceed in August of 2004.

|

So, what did we lose? The ten-story Century Building was an enormous undertaking for its time. Writing just weeks before demolition got underway, former St. Louis Post-Dispatch architecture critic Bob Duffy stated: "It is not an ordinary 19th century commercial building. The marble-finished exterior is elegantly proportioned and intelligently ornamented. While perhaps not as mythologically rich as its formidable federal neighbor to the east, it is considerably more graceful and inviting. To say that both deserve to be preserved is only to state the obvious." The obvious did not prevail.

Toward the end of the saga, Dick Moe reiterated his claim that the Trust had tried hard to dissuade the city from its plans and that someone else should attempt to change the intransigent political will. But it ultimately was the Trust that held the winning cards. Why didn't the National Trust for Historic Preservation use its intellect, its experience, its reputation, its local preservation partner and especially its tax credits to broker a far better project-one that would have reused both the Old Post Office and the Century Building?

A version of this article by Carolyn Hewes Toft first appeared in the Nov/Dec issue of Landmarks' newsletter