Preston J. Bradshaw, AIA (1884-1953)

|

| Preston J. Bradshaw in 1916, from Portraits of Prominent St. Louisans |

Bradshaw returned to St. Louis once more in 1905. The following year he co-founded the short-lived advertising and publishing firm Bradshaw, Kerr & Brownell, and in 1907 settled into work as a draftsman for the city's Commissioner of Public Buildings. That year he also accepted what is possibly his earliest independent commission for a house at 6248 Waterman in Parkview for Mr. and Mrs. Aldophus G. Meier. In August 1907 his father passed away at age of forty-eight, precipitating yet another early residential design, this time for his own family. The Bradshaws, who by then included Preston's four younger siblings, had been living in a comfortable house at 5159 Raymond Place (NR 9/13/02) since his final return from New York. After his father's death his aunt Margaret Kehoe moved in and Bradshaw almost immediately set about designing the family a much larger new home in the prominent Hamilton Place (NR 10/15/05).

|

| Bradshaw Residence, 5947 Clemens, 1908 |

Bradshaw quickly diversified his practice during the 1910s by aligning himself with the increasing number of automobile dealerships flooding into Midtown. Between 1913 and the 1920s he either designed or renovated nearly two dozen auto-related properties, including display rooms, offices, and garages. Most are located along Locust Street in what is now known as Automotive Row. Eight of them, including the ornate red brick

|

| Weber Implement & Automobile Company, 1919 |

As his prominence and commissions increased, Bradshaw moved out of the family home and into a house at 5339 Berlin (now Pershing) in 1913. This move was possibly in conjunction with marriage to his first wife Hazel, about whom little is known. After his mother's death in 1915, the couple moved back to the house on Clemens. Hazel is listed here in 1920 (along with two of Preston's siblings), but she either met her demise or their marriage soon ended in divorce for in 1925 Bradshaw married Hilda Werner, fourteen years his junior, with whom he would have two daughters, Nancy and Judy. By the early 1920s Bradshaw had designed spacious offices for himself in the International Life Building and began taking on the high-profile apartment and hotel commissions for which he would become nationally renowned.

|

| Vesper-Buick Automobile Company, West PineBoulevard and Vandeventer, 1927 (NR 10/2/86). Demolished. |

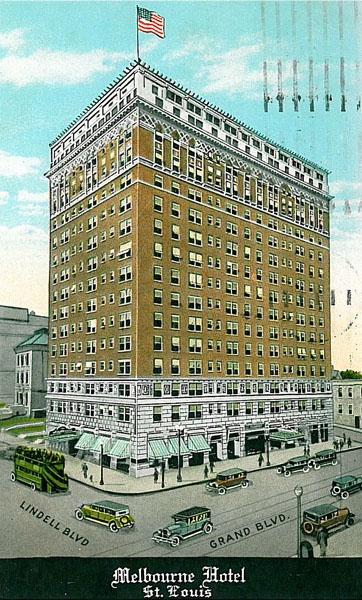

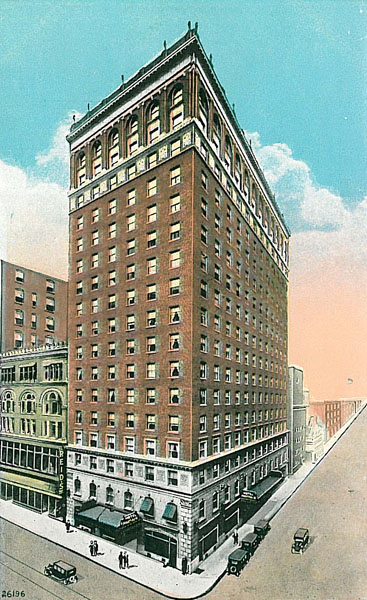

The Roaring Twenties were quite good to Preston J. Bradshaw. Just as he had capitalized on the rapid growth of the automobile industry, he cornered the market on the growing demand for high-rise, high-profile hotels and apartment buildings. The vast majority of these were located at prime locations in the Central Corridor. Most were brick with elaborate Renaissance Revival terra cotta ornamentation around their base and cornice, a basic formula which Bradshaw manipulated with each project to produce exquisitely detailed designs.

|  |

| Melbourne Hotel (now Jesuit Hall), 1921 | Mayfair Hotel, 1924 |

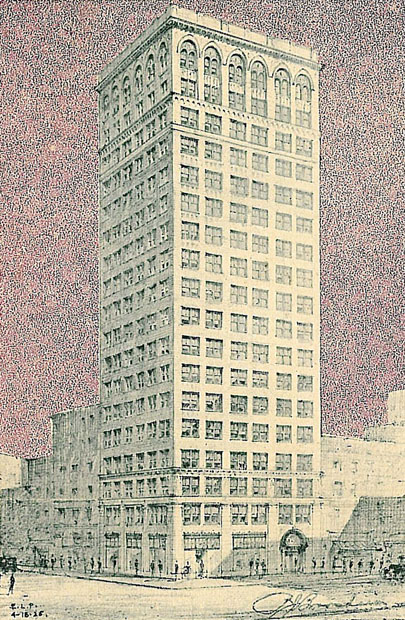

Bradshaw's first downtown hotel was the Mayfair at St. Charles and Eighth Streets in 1924 (NR 9/17/79), followed by his 1926 remodeling of floors two through ten of Tom P. Barnett's City Club Building at Locust and Eleventh Streets (NR 6/6/02) into the Missouri Hotel. On the eve of the Great Depression Bradshaw both designed and personally invested in the $2.5 million Lennox Hotel at Washington Avenue and Ninth Street, completed two months before the Stock Market Crash in 1929 and the last hotel built in the city for nearly thirty years (now the Renaissance Grand, NR 9/6/84). He also designed a number of upscale office buildings, including the Paul Brown on Eighth Street between Olive and Pine in 1925 (NR 12/12/02) and the Landreth Building at Fourth and Locust Streets in 1926 (demolished for Mansion House in the mid-1960s).

Landreth Building, 1926 |

His prolific work in St. Louis garnered national attention and drew commissions in cities throughout the Midwest and South. The St. Louis-based developers of the Melbourne Hotel enlisted Bradshaw once again in 1922 to design the $2 million Bellerive Hotel in Kansas City, the largest and most luxurious apartment hotel in that city at the time (NR 2/28/80). In 1923 Louisville lumber magnate James Graham Brown hired him to design the $4 million, sixteen-story Brown Hotel (NR 2/17/78), followed by the premier 1,500 seat Brown Theatre in 1925. Dallas' Baker Hotel (demolished 1980) also opened that year, and Bradshaw completed another design for a $5 million hotel in Detroit as well.

Though such designs dominated his practice during the 1920s, the scope of Bradshaw's work during the ensuing decade broadened as the Great Depression brought this wave of elite commissions to a dramatic halt. Luxury apartment hotels were no longer in demand for obvious reasons, and Bradshaw took on designs for smaller-scaled projects throughout the St. Louis region. The most notable of these include the Renaissance Revival style St. Philip Neri Roman Catholic Church, completed in 1931 at 5076 Durant in Walnut Park, and the Art Deco Chase and Medical Arts Buildings, completed in 1935 and 1939, their distinctive buff brick and terra cotta facades with black Vitrolite storefronts overlooking Maryland Avenue between Kingshighway and Euclid. Bradshaw also served as a consulting architect on the team chosen to design Memorial Plaza downtown.

|

| Coronado Hotel, 1922-1926 |

In 1940 the Bradshaws, Aunt Margaret and all, moved from 5947 Clemens to a large chicken farm in Gray Summit, Missouri which he named Bradfield Farms though Bradshaw maintained an apartment in the Coronado (by then the Sheraton) Hotel, which he had managed since 1925. He seems to have spent these last years of his life taking things easy, and new commissions were few and far between.

|

| Ford Apartments, 1948-1950 |

Preston J. Bradshaw died on December 6, 1953, leaving behind him one of the most important architectural legacies in St. Louis. An almost inordinate number of his buildings have been placed on the National Register of Historic Places based on their architectural significance, many of which were listed relatively early on in the 1970s and 1980s. His designs were covered in the most prominent architectural publications in the nation, and the scope of his nearly fifty years' worth of work stands a testament to his innovation and mastery of architectural style and form.