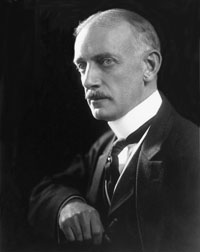

John Lawrence Mauran, FAIA (1866-1933)

John Lawrence Mauran |

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, John Lawrence Mauran entered Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1885 as a student of electrical engineering but switched (according to notes in the AIA archives) to architecture in his sophomore year. “I had my wires crossed with Course IV.” It was a fortuitous decision. By his final year in school, he had received several design awards and been elected editor-in-chief of Technique—the chatty campus newspaper which provided journalistic expertise displayed to advantage later in his career. Mauran also had the good fortune to be in Boston during the tenure of Eugene L′etange—a transplant from l′Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His eighteen years at MIT as head of design established the school’s preeminence and tilted the direction of American architectural training toward the Parisian model.

After a year of post-graduation travel and study abroad, Mauran returned to Boston and entered the office of Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge—renown successors to architect Henry Hobson Richardson. Two years later in 1892 the firm sent him to its booming Chicago branch where he gained invaluable experience working on the Public Library and the Art Institute. Soon after transfer the following year to Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge’s St. Louis office, he became a local partner (1895) involved with the firm’s prestigious residential commissions in the Central West End along with three monumental buildings on burgeoning Washington Avenue (now the Loft District) and an impressive new chapel for Second Presbyterian Church at Taylor and Westminster. Two additional indicators of Mauran’s personal and professional success in his newly adopted hometown occurred during the last year of the 19th century. One was his participation in the national convention of the American Institute of Architects as an official St. Louis delegate; the other, his marriage to socialite Isabel Chapman.

Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge closed its St. Louis office in 1900, leaving Mauran and two other employees (Ernest J. Russell and Edward G. Garden) to form a successor firm and assume control of the work-in-progress. Thanks to Mauran’s contacts, the new firm quickly carved out a niche designing Carnegie libraries for small Midwestern towns. (Known examples can be found in Missouri, Wisconsin and Kansas.) This specialty would soon prove useful at home.

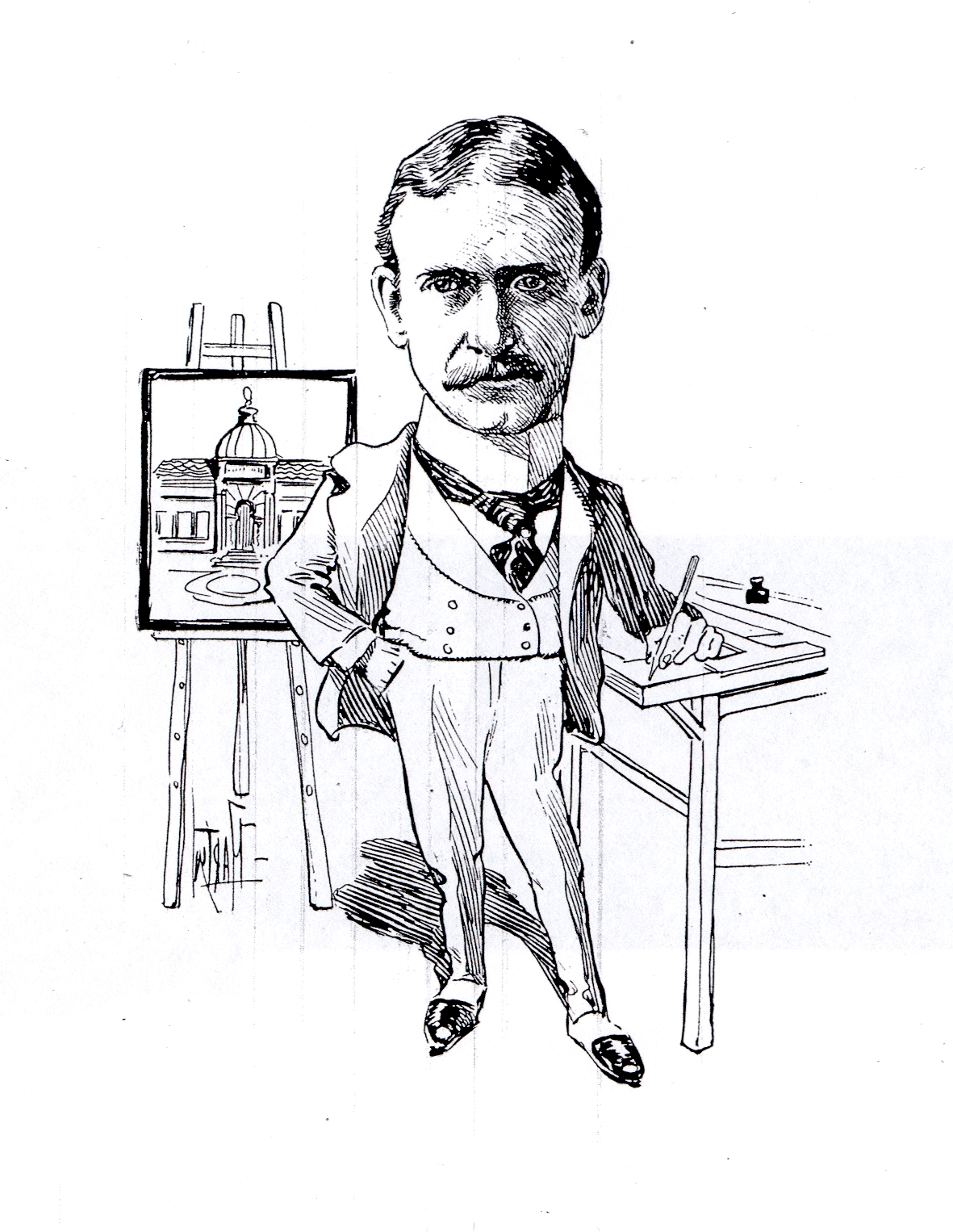

The building depicted in Mauran’s patrician caricature from St. Louisans as We See’ Em (an early 20th century in-the-know publication depicting the city’s elite) is probably the Cabanne Branch Library (1106 Union Boulevard)—the second Carnegie branch completed in St. Louis.

The building depicted in Mauran’s patrician caricature from St. Louisans as We See’ Em (an early 20th century in-the-know publication depicting the city’s elite) is probably the Cabanne Branch Library (1106 Union Boulevard)—the second Carnegie branch completed in St. Louis.

Anticipating the massive infrastructure needed for the upcoming St. Louis World’s Fair, the newly ambitious Laclede Power Company hired Mauran, Russell & Garden in 1901 to design a high-profile power plant (1240 Lewis) on the near north riverfront. Later commissions from that year included a much-praised, terra cotta-clad commercial building at 1015 Washington Avenue. In 1903, Nelson C. Chapman (wealthy scion of a lumber baron, co-owner of the Chemical Building at 721 Olive Street and Isabel Chapman Mauran’s uncle) hired the firm to prepare plans for an addition to Henry Ives Cobb’s then critically unpopular but virtually new Chemical Building.

Included in the seamless expansion of what is now one of downtown’s favorite landmarks was the firm’s handsome new suite of architectural offices high atop the undulating seventeen-story skyscraper.

By now, Mauran was gaining a national reputation. Elected President of the St. Louis Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1902 and 1903, he served as a delegate to the 1903 International Congress of Architects in Madrid. His January 1904 article in The Brickbuilder (accompanying an elaborate Beaux Arts scheme for a “suburban clubhouse” overlooking the Meramec River) revealed a new found but secure grasp of local materials and regional geography. Explaining why design solutions from New England – “The Hub of the Universe” – could not merely be extrapolated to St. Louis, Mauran noted that:

The climate, however, has affected the architecture of hall and cottage alike, for as wood construction is neither cool enough nor sufficiently durable, and native granite difficult to quarry, the local material, clay, has lent itself admirably to a brick and terra-cotta expression of the solution of the same problem in "sunny Missouri," worked out so many years ago in Spain and Italy.

The firm’s unsurpassed mastery of diverse materials is evident in a remarkable collection of institutional and commercial buildings designed in the first decade of the 20th century. A cluster can be seen in the Holy Corners National Register Historic District on North Kingshighway near McPherson: the First Church of Christ Scientist (1903), the Racquet Club (1906) and Second Baptist Church (1907). A masonry extravaganza executed in subtle shades of Hydraulic Pressed Brick, Second Baptist was published in the October 1908 issue of The Architectural Record.

More work from the firm lies a few blocks north of Holy Corners: the former Smith Academy & Manual Training School (5407-51 Enright Avenue) from 1905 and the impressive pink granite Pilgrim Congregational Church (826 Union Boulevard) from 1906. Meanwhile, in downtown, the firm had completed plans for the massive Butler Building occupying the entire city block between 17th, 18th, Locust and Olive Streets and the up-to-date Grand Leader Department Store (later Stix, Baer & Fuller, then Dillard’s and now slated to become The Laurel condominiums) on Washington Avenue at 6th Street. Demonstrated success with this emerging building type resulted in yet another Mauran-penned article (“The Department Store Plan”) for The Brickbuilder. Journals also published the experimental Lesan-Gould Building (1320 Washington Avenue) from 1907—an early, forthright expression of reinforced concrete construction with only minimal Arts & Crafts decoration.

Most of the aforementioned work shows the talented hand of Edward G. Garden—the firm’s Canadian-born, Chicago-trained designer/delineator. His Arts & Crafts influence can also be found in the contemporaneous residential work including #12 Portland Place (which got underway in late December 1905), the 1907 house at #19 Washington Terrace (a larger version of the front-gabled house Garden would design that same year for his own family) and #34 Portland Place from 1909.

One of the firm's most innovative St. Louis commissions toward the end of Garden’s tenure was the 1909 Parkway Dwellings (later, the Chouteau Apartments)

at 4973-43 Laclede Avenue—a rather formal Beaux Arts composition featuring the city’s first two-story, double-deck apartments. Then, in spite of having just settled into his own house at #23 Windermere Place, Garden (for as yet unknown reasons) left the firm on May 1, 1909. After a very short stint practicing alone from an office on the 11th floor of the Chemical Building, he packed up his family and headed to San Francisco.

Although Edward D. Garden was probably the firm’s favored designer during the nine-year partnership, Charles C. Savage in Architecture of the Private Streets of St. Louis pointed out Mauran’s predilection toward more traditional English styles. Several residential examples include the “cottage” at #10 Portland Place from 1908 as well the Charles A. Stix House at #26 Portland Place from 1909.

|

#10 Portland Place #26 Portland Place Photos by Robert C. Pettus |

An even more obvious case in point is the 1907 Church of the Messiah Unitarian at 800 Union Boulevard. As President of the Board of Trustees that voted to sell the peerless Peabody & Stearns Gothic Revival church in midtown, Mauran probably drew plans for the new church pro bono.

|

Church of the Messiah. Photos by Gary Tetley |

The pastor’s words at the dedication of this unassuming Gothic Revival replacement reinforced the architect’s special connection to the new building: “We feel it is the work of our own hands and are correspondingly proud of it and attached to it.”

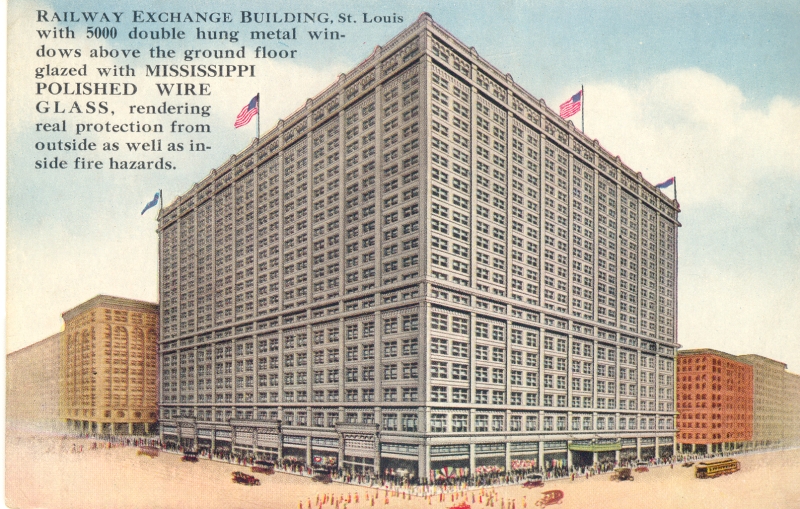

Mauran and Russell practiced together until William DeForrest Crowell (a recently acquired member of the firm trained at MIT and l′Ecole des Beaux-Arts) became partner in 1911. That same year former client Laclede Power returned to the firm with a request for a corporate headquarters reflecting the company’s prosperity. The result was a refined but lavishly detailed, ten-story headquarters at Olive and 10th Streets. A far more assertive image is evident in the firm’s Railway Exchange Building (now housing Macy’s Department Store) from 1913—a full city block clad in white glazed terra cotta.

In 1915, Mauran became the second St. Louisan elected to the American Institute of Architect's highest office. The first, William S. Eames, who died in March of 1915, had ascended to the presidency in a period of optimism and prosperity. Mauran inherited growing discontent within the Institute and an ominous conflict in Europe. By the summer of 1917, peace seemed ever more remote as America prepared to enter the World War I. (Professional journals repeated warnings from the British and French not to commit technically trained men to the trenches; with more than 100 members of the Royal Institute buried in foreign soil, the Architectural Association of London had been forced to open a school of architecture for women.)

As President, Mauran offered the Institute’s service to the country—confident that the profession’s special skills would be appreciated. Instead, engineers and contractors were hired to design hospitals, barracks and workers’ housing; even the architect’s committee on medals and insignia was overlooked. Only the American Red Cross seemed to want something of value from architects: laundered linen drawings that could be transformed into superior bandages.

Frustrated and mortified, The American Architect’s new editorial team declared war on the American Institute of Architects in late 1917—labeling it dormant if not terminal The next issue included a long, rebellious letter written by Thomas Crane Young—a former President of the St. Louis Chapter and supposedly Mauran’s colleague—in support of the journal. Meanwhile, Mauran spent more and more time in Washington, paying railway fares and hotel bills out of his own pocket. His bulletins designed to keep the unhappy membership apprised of its leaders’ dogged but discouraging efforts to participate in mobilization only made some of them more churlish since building at home had virtually ceased.

Laclede Gas Light Company Building. Photographs by Gary R. Tetley.

The Institute’s 1918 national conference in Philadelphia attracted fewer than 100 delegates. In an atmosphere charged with anarchy and bitter disillusionment, Mauran, after announcing his intentions to deal with the “stern reality of things as they are, and not as we would have be,” outlined a chronology of dashed hopes balanced by few accomplishments. He then turned to imputations that somehow the AIA’s executive committee had failed to inculcate the proper appreciation of the profession with official Washington, suggesting instead that the fault lay with

"...us as individual architects rather than with the professional body of which we are component parts.... Have we stood shoulder to shoulder with the budding politician in civic activities... or have we held aloof only to be drawn into some City Beautiful movement, born but to die, because we do not insist that our talents are dedicated to the City Practical-and in our professional practice with these officials in their capacity of private citizen and fellow townsman, have we established through efficient and capable professional service rendered, that deep-seated conviction of the administrative ability of an architect, or has the Congressional conception of an architect as a dreamer and long-haired creator of useless but expensive dewdaddles come to the Capitol only from the supervising architect's office?"

A motion to amend the Institute’s bylaws to allow John Lawrence Mauran to serve a third term failed.

Postcard view of the Railway Exchange Building from Landmarks' collection. |

Mauran, an exemplar (as was his partner Ernest John Russell) of the sort of civic involvement he urged upon other architects, returned home to an unblemished community reputation. Having been invited as a newcomer to join all of the right clubs, Mauran was active on important philanthropic boards and had assumed major roles in Progressive-era public policy efforts even before the precedent-setting 1907 Civic League City Plan. Important new civic responsibilities would include heading up the Memorial Plaza Commission, formed in 1925.

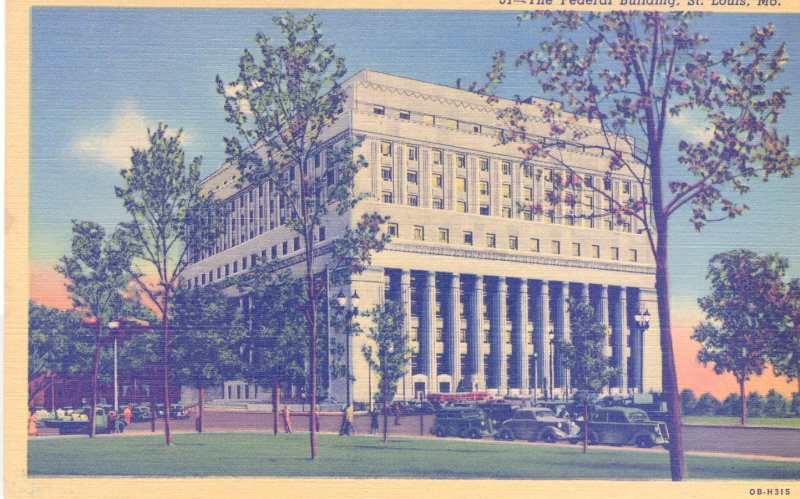

It seems clear, however, that control of the firm’s aesthetic was shifting to William DeForrest Crowell. Although Crowell had joined one of the best-connected and respected firms in the Midwest, his training in marine design and his fascination with aviation would soon be evident in the firm’s new portfolio of streamlined Art Deco/Moderne buildings for large corporations and government entities. The first, the Federal Reserve Bank from 1923, was followed by Union Market (1924) and then by the Police Headquarters (1927) and its neighboring Police Academy (1928). In late 1930, Mauran, Russell, Crowell & Mullgardt (W. Oscar Mullgardt became partner in 1929) received word that they had been selected to design the new Federal Building in San Francisco; in 1931, the opening of the firm’s new St. Louis Globe-Democrat Building rated a congratulatory note to the newspaper’s publisher from President Herbert Hoover. Work on St. Louis’ new Federal Courts Building got underway in 1932.

|

Postcard view of the Federal Building from Landmarks' collection. |

On September 23, 1933, Mauran died suddenly from peritonitis suffered after an appendicitis attack at the family’s summer home in Rhode Island. Only sixty-six years old, he was survived by his wife and two daughters, Isabel Lawrence and Elizabeth Chapman, and the cherished St. Louis residence. The young couple had moved into her family home at #46 Vandeventer Place (designed by Eames & Young) upon their marriage in 1899. At that date still the most prestigious address in town, the private street soon became a threatened residential enclave hemmed in by commercial development and transit. That Mauran, who could have lived anywhere, stayed and apparently added only a library to an 1892 house designed by a competitor for his in-laws can be viewed as the decision of a man with self-possessed equanimity and sangfroid.

R. Clipston Sturgis, former President of the American Institute of Architects, read a long tribute to Mauran at the 1934 AIA convention in Washington:

His whole life has been a remarkable example of how a man can practice with success an absorbing and difficult profession and yet find time for constant and continuous service to that profession and widespread service in other fields and have time to spare for all the amenities of life. One of the remarkable qualities of Mr. Mauran was his unfailing humor and light-heartedness.

It was St. Louis’ Unitarian Church of the Messiah, however, which paid him the most eloquent honor. In 1934, the congregation installed a bronze tablet bearing the same epitaph as one over the tomb of architect Christopher Wren in St. Paul’s Cathedral, London: Si monumentum requiris, circumspice. “If you seek his monument, look around you."

An abbreviated version of this article written by Carolyn Hewes Toft first appeared in the September/October 1984 Landmarks' newsletter.