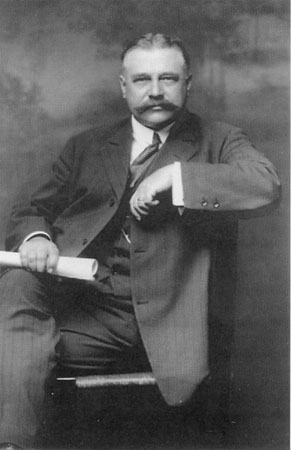

George Edward Kessler (1862-1923)

|

Two-year-old George Edward Kessler and his financially secure parents (Clotilde and Edward Karl) immigrated in 1865 from historic Bad Frankenhausen, Germany through New York and then on to Dallas, Texas—a recently disarmed Confederate stronghold with a frontier population of no more than 3,000 inhabitants. Once settled, Edward apparently invested in a nearby cotton plantation. Although securing rail service in the early 1870s would soon put Dallas and King Cotton in a strategic trade position, Kessler senior died in 1878. His widow decided to return to Europe so that George could be trained for a proper career.

The study of forestry, botany and landscape design began in the Grand Ducal Gardens at Weimar. Courses at the Charlottenburg Polytechnicum were next, followed by a year in civil engineering at the University of Jena. Kessler, under the direction of a private tutor, spent the last of his three propitious years abroad investigating the civic design of major cities from Paris to Moscow. Back in New York in 1882, while working for a seed company, he contacted Frederick Law Olmsted who located a challenging assignment in the West—laying out a pleasure park in Merriam, Kansas, just eight miles via the Kansas City, Fort Scott & Gulf Railroad from Kansas City, Missouri. This assignment grew to include work at all the stations and at a railroad tree farm.

Impressed with young Kessler's accomplishments at Merriam Park, the fledgling Kansas City Board of Park & Boulevard Commissioners hired him as "Secretary" (at a meager $200 per month) in March of 1892. Kansas City, a rapidly growing metropolis blessed with what Kessler called "an eccentric topography," had imposed a rigid gridiron on its street system. In 1893, Kessler handed the Board a bold plan for a grand system of interwoven boulevards and parks that enhanced, rather than ignored, geography. Amazingly, the entire City Beautiful proposal would be implemented by 1915.

Meanwhile, Kessler had married Ida Grant Field of Kansas City in 1900, become a consultant to the Kansas City Park Board and moved temporarily to St. Louis as landscape advisor (along with junior architect Henry Wright) for the 1904 World's Fair. Interview notes written during the fair hint at a fluid working arrangement that sometimes favored Kessler over the architectural team:

The great building scheme, as arranged by the Commission of Architects and with the Director of Works [architect Isaac Taylor], was based on regular street lines. In order to break the monotony of barren streets, even with the presence of the lagoons, I secured the approval of the planting of avenue lines of trees along the lagoons and the Plaza of Saint Louis. In some cases architects made some objections to placing the trees, with the idea that they would screen the buildings from view. The completion of the picture, however, has demonstrated the value of these trees in framing the building in daylight, and at night the lights filtering through the foliage adds immensely to the beauty of the picture.

As required, the city brought Kessler (and Wright) back to repair the park after the wildly successful exposition shut down in December 1904; by 1906, Kessler's drawings carried a joint St. Louis/Kansas City address. Wright worked from the St. Louis office with Kessler on a 1906 plan for the Vanderbilt campus in Nashville. Both men (and Surveyor Julius Pitzman) were heavily involved in the 1907 Civic League Plan for St. Louis which envisioned a necklace of new outer parks linked by a twenty-five-mile-long boulevard to another boulevard designed to connect existing city parks. Another version of that concept prepared in 1907 for the hilly city of Cincinnati, Ohio would provide a lasting foundation for its future.

Local commissions from 1907 (landscaping for Mauran, Russell & Garden's new Christian Science Church and Cabanne Branch Library as well as elaborate gardens for Westmoreland, Vandeventer and Portland Place clients) illuminate the degree to which Kessler had ingratiated himself with the city's Central West End elite through professional and volunteer collaboration in the World's Fair and the Civic League plan.

|

In 1908, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Directors engaged Kessler & Wright to design a commemorative pavilion where the Fair's Missouri Building had stood (the "Rest House" pictured above) and Indianapolis brought Kessler in to begin work on a comprehensive park and boulevard system. After the plan was adopted and enabling legislation passed, Indianapolis retained Kessler to oversee implementation. Similar commissions for Fort Worth and Dallas, Texas, Denver, Colorado and Pensacola, Florida got underway in 1909.

By now considered the country's leading landscape architect/city planner, Kessler moved his family to St. Louis in 1910—residing first in the prestigious "ABC Apartments" on Kingshighway overlooking Forest Park. Within a few years he purchased John David Davis' house at #51 Vandeventer Place across the street from client/colleague John Lawrence Mauran. Earlier association with Davis may well have been the key factor in Kessler's permanent move to St. Louis. Plutocrat Davis had chaired the Civic League's park committee which advanced the following exhortation in the 1907 plan:

While parks are of inestimable value in making a city inviting to desirable residents and visitors, furnishing pleasant drives to those who can afford these luxuries, adding to the value of real estate, and promoting the general prosperity, these are matters of small consideration when compared to the imperative necessity of supplying the great mass of the people with some means of recreation to relieve the unnatural surroundings in crowded cities.

The men who drafted that plan knew those who drafted legislation; the necessary act was passed by the State Legislature in time to place a proposition on the November 1910 ballot. Although St. Louis city's "Kingshighway Belt Boulevard" vision remained intact, the outer park proposal had been pared down to three sites: the picturesque Meramec Highlands southwest of the city; the bluffs affording magnificent views of Creve Coeur Lake; the strip of bluffs overlooking Chardonnier Island in the Missouri River.

It seems likely that Kessler had just moved to St. Louis in the expectation that the proposition would pass in the city and the county. It failed in both. Supporters blamed the massive number who turned out to vote a resounding "NO" on another proposal favoring Prohibition.

In 1911, Dwight F. Davis, Chairman of the Civic Centers Committee for the 1907 plan, became St. Louis Park Commissioner. A staunch disciple of the good citizenship through recreation doctrine, "...the primary purpose of the park system should be the raising of men and women rather than grass or trees" [as quoted in the Park Commissioner report of 1915], Davis worked with Kessler to develop a landscape plan for Forest Park that concentrated formal floral displays in prominent locations and left large tracts of land open for lawn, athletic fields and golf courses.

Goverment Hill crowned by the new pavilion by Kessler & Wright was an obvious choice (the fountain was not added until 1930). |

An early member of the St. Louis City Plan Commission, Kessler was also a founder of the American Institute of Planners in 1917 and one of the original members of the National Commission on Fine Arts. He died on March 20, 1923 in Indianapolis and was buried in St. Louis' Bellefontaine Cemetery. The obituary in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects credited him with work in more than 40 cities and communities of the West and Middle West, "...a city planner and landscape architect of extraordinary insight, vision and practical ability."

He was also the right man with the right training at just the right moment in history. Thanks to his mother's good judgment, and her adequate income, Kessler began his career with the benefit of rigorous German technical training enhanced by the practical aesthetics gleaned from a tutored Grand Tour. This multi-disciplined education applied to a just-emerging field put him in an enviable position in comparison to the growing number of would-be American architects with actual or transplanted Beaux-Arts training. Indeed, Kessler would set the pace and the precedents for the marriage of landscape architecture and city planning in the United States, the realization of the City Beautiful and the City Practical.

Kessler was survived by his wife and son George, a student at Central High School. In 1949, George E. Kessler, Jr. donated an extensive collection of his father's papers to the Missouri Historical Society which (thanks to a grant from the William T. Kemper Foundation) is placing the trove of correspondence, invoices, drawings and photographs on microfilm. It is a collection well worth study and publication. Unaccountably, not even a footnote about George Edward Kessler appeared in American Landscape Architect: Designers and Places published by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the American Society of Landscape Architects in 1989.

An abbreviated version of this article written by Carolyn Hewes Toft first appeared in the September/October 1993 Landmarks' newsletter.