The Arch Grounds and the Old Rock House

November 1, 1940, looking west on Chestnut Street from Wharf Street. Photograph from Landmarks' collection. |

The sign on the front door of the small stone building in the photo above informed the public and the demolition contractor for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial that the Old Rock House was the property of the United States government. The National Park Service had purchased the building (an 1818 warehouse built by Manuel Lisa) in 1936. By November of 1940, the last tenants were evicted and a $22,410 Works Project Administration grant had been obtained to help turn the venerable structure into a "museum of the historic St. Louis fur trade." The project had merit.

Manuel Lisa (1771-1820) arrived in the village of St. Louis in the late 1790s. Born in New Orleans of Spanish parents, Lisa challenged the French founders' hold on the St. Louis fur trade and quickly forged a monopoly with the Indian tribes of the upper Missouri River. James Neal Primm in Lion of the Valley described "Black Manuel" as brilliant, aggressive, bold and fearless . . . an eagle among hawks" who returned generous favor and honest dealing in exchange for secure trade territory. It was this mutual trust that enabled Lisa to persuade his partners to attack and neutralize pro-British tribes during the War of 1812. A commendation for wartime activity from Governor William Clark along with Lisa's marriage in 1818 to a "lady of standing" are indicators of how rapidly one could gain social status in pioneer St. Louis.

Lisa built the rubble-stone warehouse in 1818 on a lot he had purchased for $600 in 1810, but the high risk, high profit fur business often entailed high mortgages. Five years after his death in 1820, the warehouse and a stable were finally auctioned for only $440 to settle the estate. In 1828, the warehouse was purchased by James Clemens, Jr., a cousin of Mark Twain. During the next sixty years of Clemens' family ownership, the building was home to a sail maker's shop, an ironworks store, a produce and a commission house. A saloon opened in 1880. The jaunty, out-sized mansard roof just visible in the 1940 photo above probably dated to the Victorian period as do some of the colorful bits of improbable Rock House lore. Beulah Schact, rhapsodizing in the June 8, 1958 Globe-Democrat, stated: "During the halcyon days on the river, it was known from Minneapolis to New Orleans as one of the liveliest spots along the shores. Steamboat captains and millionaires shared drinks with Mark Twain and Eugene Field."

The age of the railroad gradually changed the bustling character of the old riverfront district; the advent of the automobile brought additional decline. By 1928, Harland Bartholomew's Plan for the Central River Front, St. Louis proposed massive demolition and the creation of a great ceremonial plaza punctuated with subway terminals and loops, elevated pleasure drives and parking structures. Although the plan cited the "ragged condition" of the structures from 3rd Street to the river, it did not mention the drifters, the poverty or the seedy, socially unacceptable businesses such as the Old Rock House Saloon where an evening of nickel whisky and pig knuckles downstairs could be followed by an upstairs pad for 15 cents.

The Terminal Railroad Association rented the joint to Alex and Albina "Mom" Paintinida in 1928. The new tenants cleaned up the top floor, moved in, changed the menu and pulled in a clientele that included "socialites, newspaper people and artists." According to Mom, a mid-Depression nightclub they opened on the second floor featuring Rock House Annie and her naughty songs attracted W. C. Handy in a chauffeured limo. Band leader Wayne King headed to the Rock House to help Mom tend bar. Still peeved in 1958 about her eviction in 1939, Mom told the Globe-Democrat: President and Mrs. Franklin Roosevelt drove right up to the front of the place and stayed in their big car just looking at it. ‘Save that building' is what Mr. Roosevelt said." Maybe he did. Certainly someone of importance decreed that it be spared.

Meanwhile, in late 1933, attorney Luther Ely Smith and other local leaders persuaded Mayor Bernard Dickmann to form a committee to push for the establishment of a national memorial to the pioneers and the Louisiana Purchase. A local non-profit, the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association, was formed in 1934. President Roosevelt signed a joint resolution later that year creating a federal commission to formulate plans for the design and construction of the memorial. A flurry of local and federal actions in 1935 set up the legal framework along with a three-to-one matching formula for funding. The National Park Service opened a St. Louis office in 1936; the first condemnation suits in the 40-block site were filed the following year. Demolition contracts, however, were not let until early 1940 due to an assortment of legal challenges.

Third and Chestnut Streets, March 1, 1940. Photograph from Landmarks' collection. |

Memorial supporters had been able to extract Depression-era money from a local bond issue (the election was unsuccessfully contested) and the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act, but those funds only covered land acquisition, compensation to owners and demolition of all buildings except the Old Courthouse, the Old Cathedral and the Old Rock House. No one cared very much about a design. The country was soon to go to war; the cleared site made a dandy 4,500-car parking lot.

It was not until 1945 that local boosters could initiate a subscription campaign to finance a national architectural competition. By 1947, the requisite $255,000 was in hand and the panel of seven jurors was selected. The initial phase of the competition attracted 172 entries; a short list reduced the field to five. Harris Armstrong (1899-1973) was the only St. Louisan who made the cut and the only finalist working alone.

|

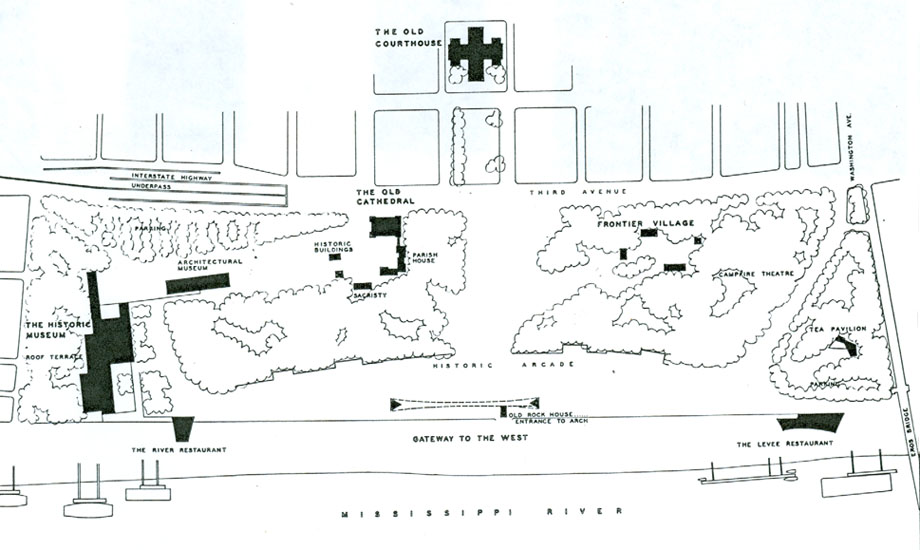

Eero Saarinen's team included an architectural associate, Saarinen's first wife (a sculptor), an artist and landscape architect Dan Kiley. Their site plan (reproduced above) from the competition's second and final phase is fascinating. Museums, forests, restaurants, a tea pavilion, a frontier village, an "historic" ensemble forming a "J" with the Old Cathedral and last, the Arch-entered from our old friend, the Rock House! So, what happened?

After the jury announced that Saarinen's scheme was its unanimous choice, the U. S. Commission approved the design and recommended to the Secretary of the Interior that Saarinen be retained. A donation of $15,000 to the Department of the Interior from the local Jefferson National Memorial Association got design development underway. Congress, however, insisted that a long-standing impasse with the railroads be resolved before releasing any dollars. Although a Memorandum of Understanding about relocating the Missouri and Terminal lines had been signed by all parties in 1949, deliberations about just how that might be achieved had proven to be complicated. Saarinen vetoed a solution that would have sent the tracks on-grade through the site, proposing instead a system of short tunnels and cuts based on the catenary arch.

Congress finally appropriated a meager $2.5 million in 1956; in 1957, the Park Service announced a site plan revision whereby the tunnel could be shortened and costs reduced. The Old Rock House was doomed. Festive groundbreaking ceremonies for the railroad relocation project were held on June 23, 1959. Within less than one week, a contract ($2,426,155) for relocation work along with dismantling the Old Rock House was awarded to the MacDonald Construction Company of St. Louis. Included in the contract was the requirement that stones from the Rock House corners and lintels be numbered and kept along with some of the timbers and hardware. (The diminutive building could not be moved as a unit. A limestone outcropping formed part of the west wall; the rest of the walls were constructed of small pieces of unstable rubble pried from the limestone bluffs.)

Perhaps the National Park Service made it clear that it would build a reproduction, not a reconstruction, of the Old Rock House at another site on the Memorial grounds. The public, however, believed otherwise. In 1965, the Post-Dispatch's E. F. Porter, Jr. began a tantalizing story: "Most of the Old Rock House is missing and presume to be lost." Porter went on to quote George B. Hartzog, Jr., Superintendent at the Memorial when the Rock House was dismantled, who stated that the entire building was not saved because most of the materials were no longer original. (The Park Service, in fact, had "restored" the building soon after acquiring it in the early 1940s.) The story concluded with comments from LeRoy R. Brown, acting Superintendent, assuring readers that a reproduction of the Rock House was to be erected at the south end of the park. Costs were estimated at $108,000; no money had been budgeted.

Hartzog's version of history and Brown's plans for the future were soundly challenged in "Two Architects Dismiss Proposal to Rebuild Old Rock House," a follow-up Porter story from 1965. Charles E. Peterson, responsible for the 1941 restoration work, said that "the historical and architectural significance of the building depended on its remaining at its original site at the foot of Chestnut Street." John Albury Bryan called the proposal to build a reproduction "valueless." (Bryan, who went to work for the Park Service in 1936, had been assigned the task of evaluating more than 400 buildings on the Memorial site. It was he who helped formulate the original requirement that the Rock House be retained.) Bryan sloughed off the salvage efforts as a public relations gesture-alleging that Hartzog was anxious to get the project going and that Saarinen didn't want the Rock House there anyhow.

Almost forty years later on Sunday, February 4, 1996, an attentive audience heard Regina Bellavia lecture at the Stupp Center in Tower Grove Park. Her topic, "Jefferson National Expansion Memorial: the Challenge of Preserving a Designed Contemporary Landscape," was a work-in-progress report. An historical landscape architect, Bellavia's first assignment with the National Park Service dealt with President Theodore Roosevelt's estate in New York. In St. Louis, her job was to document the original design intent, piece together project history and develop a long-range maintenance plan for the Memorial grounds.

Although "Whatever happened to the Old Rock House?" is a question still asked today (the partial answer: random stones can be found the basement of the Old Courthouse), Bellavia's initial research revealed a complicated authorship and evoked new questions about the integrity and/or sanctity of the as-built Memorial landscape. Some of her early findings worth pondering:

- Saarinen and Kiley's intricate lagoons complete with footbridges and islands were displaced by more formal, less intimate spaces.

- The Park Service was nervous about safety in the "forest wilderness;" so the forest became less dense.

- Saarinen envisioned the grand staircase ascending from the water's edge to the crown of the hill with treads growing smaller as the top is neared.

- Kiley specified cobblestones rather than grates around trees framing the major paths and the plant type selected was different.

Bellavia also noted that the fertile collaboration between Saarinen and landscape architect Dan Kiley lasted from the 1947 competition through many design evolutions to Saarinen's death in 1961. The Park Service then chose not to retain Kiley on his own, depending instead upon in-house personnel to complete the design and monitor construction.

Regina Bellavia's 250-page Cultural Landscape Report for Jefferson National Expansion Memorial published later in 1996 (copies available in 2007 from the National Park Service in St. Louis) is an invaluable resource for readers interested in the relationship between Saarinen and Kiley (they first met in 1942 thanks to architect Louis I. Kahn) and the convoluted history of their vision for St. Louis' Memorial.

A version of this article by Carolyn Hewes Toft first appeared in the January/February 1996 issue of Landmarks' newsletter.