Thomas Crane Young, FAIA (1858-1934)

|

| Thomas Crane Young circa 1925. |

Born in Sheboygan, Wisconsin in 1858, Thomas Crane Young moved with his family to Grand Rapids, Michigan where he graduated from high school. Young had demonstrated an early aptitude for drawing and worked during high school vacations in the office of a "country" architect.

After two years clerking full-time for the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad, he came to Washington University in St. Louis thanks to a scholarship provided by George Partridge. An 1879 drawing by Young for Smith Academy was published in the American Architect and Building News with a note that the building was "now in the course of construction at the corner of 19th and Washington Avenue."

After just two years (1878-80) at Washington University, Young left for Europe. "A small legacy and several hundred dollars in prizes won in architectural work" enabled him to study at l'École des Beaux Arts in Paris and at Heidelberg University in Germany. Upon his return to the United States, Young worked from 1882 until 1885 in the Boston offices of Van Brunt & Howe and E. M. Wheelwright.

|

| Smith Academy, demolished. |

|

| Robert S. Brookings residence, demolished. |

|

| 46 Vandeventer Place: Joseph G. Chapman residence, built in 1892, demolished in 1948. |

He then returned to St. Louis to undertake a commission for a small office building for Dr. John Green. William S. Eames supervised that construction and the two men formed a partnership later that year. Two houses by Eames & Young from 1885 remain; the Charles T. Clark residence stands at 3757 Westminster Place, and the Halsey Cooley Ives residence, designed for the first Director of the Museum of Fine Arts, stands at 3424 Samuel Shepard Drive. Other residential work for important clients, such as an 1888 house at 2329 Lucas for Robert S. Brookings, led to commissions in that bastion of exclusiveness, Vandeventer Place, and the newly opened private streets in the Central West End.

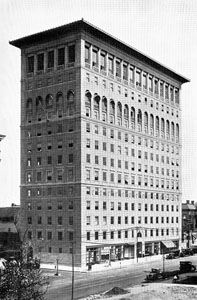

By the end of the century, the firm had gained important commissions for other building types including the Cupples Warehouse complex for Brookings, the Lincoln Trust Building (Title Guaranty), the Art Building for the Trans-Continental Exposition in Omaha and federal prisons in Atlanta, Georgia and Leavenworth, Kansas.

Excerpts from a paper read by Young at the 1899 American Institute of Architects meeting convened in Pittsburgh shed light on contemporary conflicts within the profession: "Something more than mere assertion should be required of those who would convince us that the only fit training for architects is to be acquired at l'École des Beaux Arts; that architecture as an art exists today only in France or that the pupils of this school have a corner on the world's supply of architectural ability."

Young specifically attacked the school's tradition of elaborate and costly drawings and a related "vice" perpetuated by its graduates: competitions. "This practice, even in its least objectionable form, is undignified in the extreme and cannot be defended by any of the rules of reason or common sense. What other class of men except architects could be induced to risk the money, time and nervous force involved in these expensive contests on so slim a chance of return of the capital invested, to say nothing of the prospective profits? Except on the Wall Street curb or country race track, it would be hard to find a parallel case of financial rashness. Those of us who in this matter would like to be on both sides of the fence compromise on calling the practice a necessary evil and accept the situation much as did the people of the Middle Ages look upon the periodical visits of the plague."

|  |  |

| Frisco Building, 1903-1904. | Meysenburg residence, 5 Westmoreland Place, completed in 1892. | Boatmen's Bank Building (now the Marquette), 1913-1914 |

Young's paper was prepared on the heels of the firm's unsuccessful entry for the new Washington University hilltop campus. (Cope & Stewardson of Philadelphia had been selected as the winners on October 27, 1899. In addition to Eames & Young, other submissions came from Cass Gilbert, McKim, Mead & White, Carrere & Hastings and Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge).

|

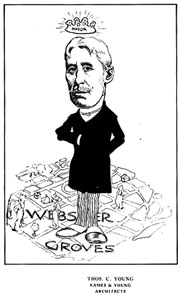

| Caricature of Young in Saint Louisans As We See 'Em, 1903. |

Young served as Mayor of Webster Groves from 1901 to 1903 and as President of the St. Louis Chapter of the American Institute of Architects from 1909 to 1910. By the time of Eames' death in 1915, the firm's national reputation was solidly entrenched. Young continued to practice after Eames' death and apparently formed an office in Chicago with Alfred H. Granger, formerly of Frost & Granger, in 1917. His last St. Louis building (1921-26) was the Masonic Temple on Lindell in collaboration with Albert B. Groves.

On February 25, 1927, the St. Louis Chapter of the AIA presented a testimonial dinner in Young's honor. Held at Eames & Young's University Club Building, the dinner's extensive program featured talks on the following subjects: "The Work of Eames & Young," "Architecture--a Civic Asset," "The Architect's Duty to the Public," "The Work of St. Louis Architects from the Layman's Point of View," and "The Profession of Architecture." For that occasion Cass Gilbert (who had won two competitions entered by Eames & Young--The St. Louis Public Library and the Minnesota State Capitol) prepared the following assessment of his rivals: "Their residential work is always especially interesting. A strong personal quality, sometimes picturesque, sometimes quiet and serious, but always vital and interesting. Their monumental work is distinguished, scholarly and notable, ranking among the very best of our time."

|  |

| University Club, 1915-1918. | Masonic Temple. |